2025-12-08

Daniel Hartman

Design Dispatch, New York

In the automotive world, most designers spend their careers in one discipline; exterior, interior, user interface, or color and materials. This structure has produced world class expertise and continues to define how the industry works.

But this specialization can sometimes create coordination challenges that extend development timelines or lead to compromises. Traditional automotive development often follows a sequential handoff model: exterior designers create a form, then interior teams must work within those constraints, often limiting spatial efficiency. Later, UI designers try to integrate screens into predetermined architecture, sometimes resulting in awkward placements that prioritize aesthetics over usability. Industry data suggests that design changes made during prototype phases can cost 10-15 times more than changes made during initial concept development.

Some designers take a different route. Jessica Suh, Design Team Lead at IDEENION Automobil AG in Germany, has built her career by rotating between fields instead of staying in one. That path, she says, later became an unexpected advantage when she began directing entire vehicle projects.

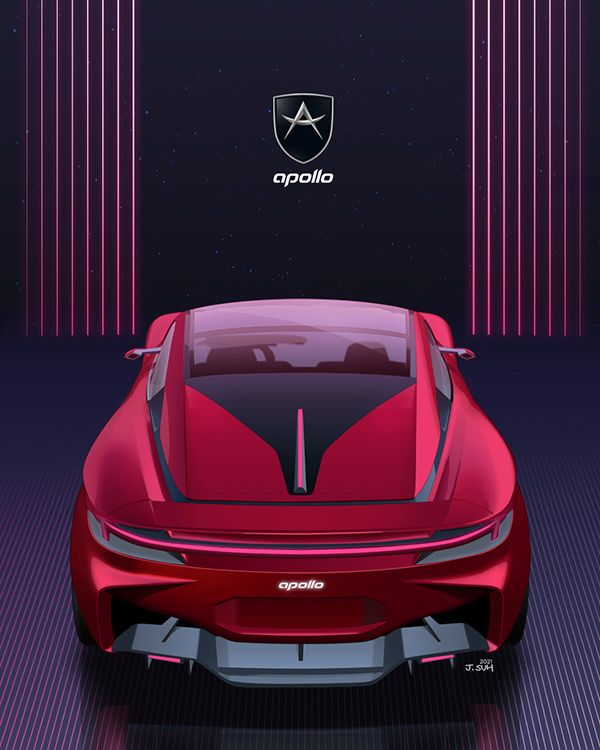

Suh’s portfolio illustrates the range. She led exterior design on Apollo’s EVision S, worked on color and materials for the sustainable XBus camper, and took on interface design for Apollo’s GJ2. At UME, she contributed across branding, exterior, interior, and even storyboard animation for the user interface. Each project demanded a different lens, and moving between them became a foundation for her leadership.

“These experiences meant I was always switching perspectives,” she recalls. “Iit also taught me how every decision connects to the rest of the car. Exterior taught me about proportions, CMF taught me how materials tell a story, UI showed me the logic of interaction. Later, when I directed a full program like the AUO Smart Cockpit, that mix helped me connect everything into one coherent story.”

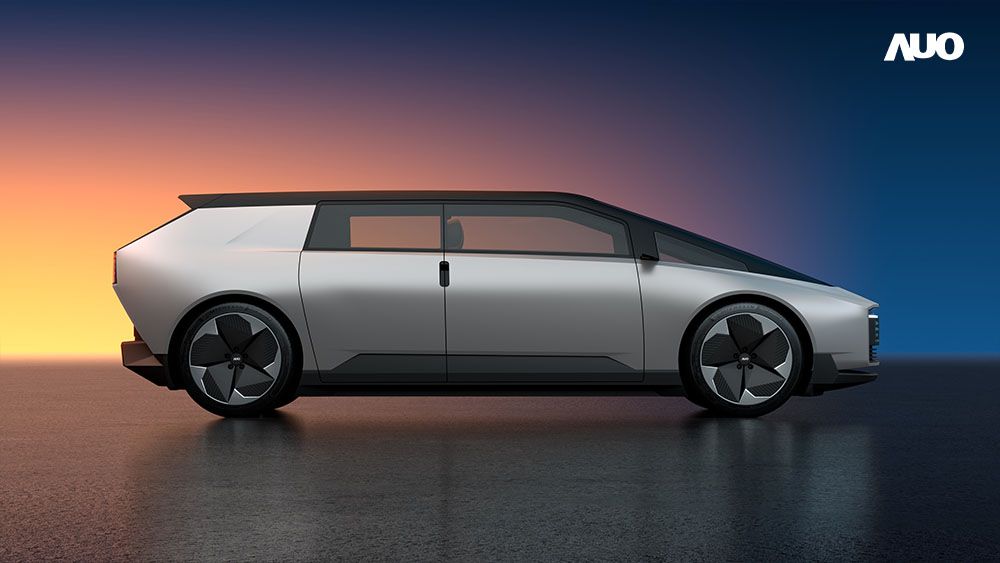

The AUO Smart Cockpit, showcased at CES 2025, required integrating six different displays into a unified experience. Working with her design chief, Suh focused on ensuring that digital elements and physical architecture worked in harmony. On this project, her integrated approach proved essential. Rather than designing six separate displays and hoping they would work together, she could anticipate how the roof display’s curve would affect viewing angles from rear seats, or how the driver display’s brightness might interfere with the ambient lighting scheme.

“Traditional approaches would have required multiple coordination meetings between teams to resolve these conflicts,” she explains. “By understanding all the disciplines involved, I could address these interactions from the initial design phase.”

This approach has constraints that Suh readily acknowledges. Deep technical expertise still requires specialization. She relies heavily on specialists for complex engineering validation. The challenge is knowing when to defer to expertise versus when cross-disciplinary perspective adds value.

“I’m not trying to replace specialists,” she emphasizes. “It’s about having enough empathy to connect the pieces. When an engineer tells me a particular curve is impossible to manufacture, I want to understand why so I can learn from it and apply that knowledge to future projects. That way, when similar challenges arise, I already know what to anticipate and can discuss solutions with the team from the very beginning.”

Her perspective echoes broader research in concurrent engineering and multidisciplinary optimization, which shows that integrated workflows can accelerate development by 30 to 50 percent while maintaining quality. Beyond timeline improvements, this approach reduces costly late-stage revisions and minimizes coordination overhead between teams.

Suh’s journey reflects what may become a broader opportunity for the automotive industry. Around the world, design schools are beginning to experiment with rotation-based curricula, encouraging students to move between disciplines rather than specialize too early. As vehicles evolve into software platforms with hardware interfaces, the traditional boundaries that once separated exterior, interior, and digital design are becoming less relevant than the ability to orchestrate integrated experiences.

“It’s incredible to see how fast the tools are developing,” Suh says. “With AI and 3D modeling advancing so quickly, I look at students’ work today and it feels like watching Avatar. They’re designing entire vehicles by themselves. The understanding of how to design a complete car is becoming more common, and that’s exciting because cars are no longer just machines. They’re environments where form, technology, and materials have to come together seamlessly.”

Several major automotive companies are quietly experimenting with similar cross-functional design approaches, though most still maintain traditional organizational structures. The question, Suh says, isn’t whether specialization will remain important. It will, but whether rotation and cross-disciplinary fluency will become additional competitive advantages in the years ahead.

For Suh, her own path illustrates this evolution. “Specialization is the foundation of good design,” she says. “But having experience across different fields gives you perspective. It helps you understand how one decision affects another.”

She gives a practical example: “When you know how material selection affects the radius of an interior corner, or how manufacturing limits can change the shape you want to achieve, you design more intelligently. Even small details like screw dimensions can affect how components come together. Because I’ve experienced those constraints firsthand, I can identify potential issues early and make the process faster and more accurate so the team can focus on perfecting execution rather than fixing problems later.”

Suh believes this mindset. A combination of empathy, curiosity, and technical understanding represents the future of design. “I was lucky to have those chances early in my career,” she says. “They gave me the tools to connect disciplines and lead whole-vehicle programs with confidence. The industry will evolve in its own way, but integration will always be at the heart of progress.”

As cars become more digital, interactive, and global, the most valuable designers will be those who can see the whole picture. People who understand not just how something looks, but how it feels, functions, and fits into human life.

Jessica Suh’s career proves that integration is not the opposite of specialization, but its evolution. By bridging disciplines, she’s showing that the future of automotive design will belong to those who build connections. Not just cars.

Her vision also points to a deeper shift in how creativity itself is defined. In an age where technology increasingly automates execution, human creativity will lie in the ability to synthesize to bring together art, engineering, and empathy into one cohesive experience. Designers who can translate between these worlds, as Suh does, won’t just design vehicles; they’ll design the ecosystems of mobility that shape how people live, move, and connect in the decades ahead.