2025-09-05

Sarah Chen

Design Dispatch, New York

Choreographer-researcher Yeji Moon reframes K-pop cover dancers as cultural archivists—foregrounding identity, transformation, and self-authorship through a compelling photographic exhibition.

Yeji Moon, a choreographer, visual documentarian, and performance researcher, merges her extensive background in Korean traditional and contemporary dance with critical inquiry in diaspora studies. Her latest exhibition, Becoming the Other, Becoming Myself: Visual Archives of Diasporic K-pop Bodies, is a culmination of that interdisciplinary practice—a powerful visual project that bridges choreographic insight with cultural critique.

Trained across dance and ethnographic methods, Moon moves seamlessly between the roles of creator, interviewer, and curator. Her unique approach to K-pop cover dance not only legitimizes it as an artistic and sociocultural form but also amplifies the voices of diasporic performers too often dismissed by both academia and the arts.

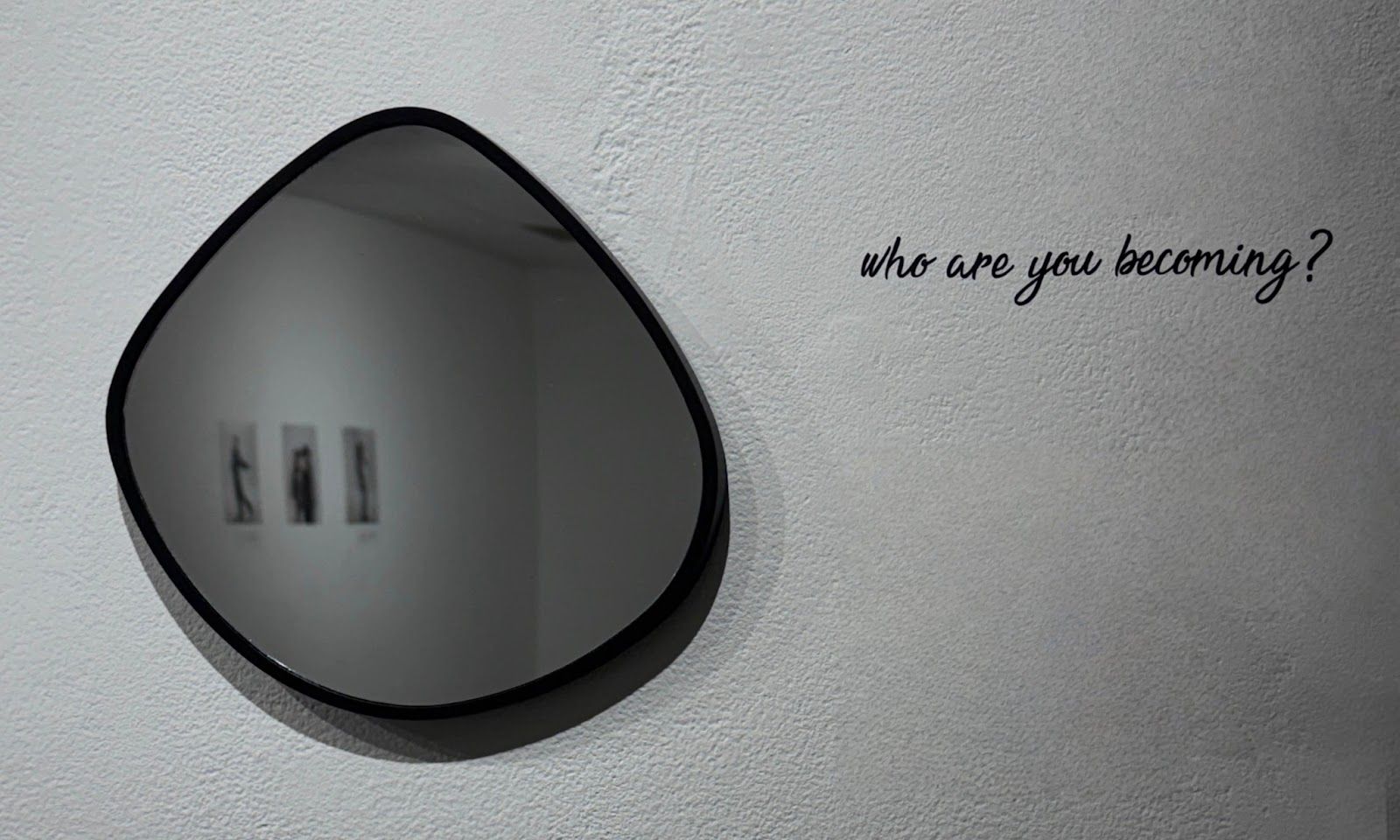

In Becoming the Other, Becoming Myself, Moon turns her gaze not on the stars of K-pop, but on those who become them—if only for a moment. This is not an ode to celebrity, but a deeply considered reflection on how diasporic youth use cover dance to navigate identity, negotiate belonging, and construct embodied archives of cultural participation.

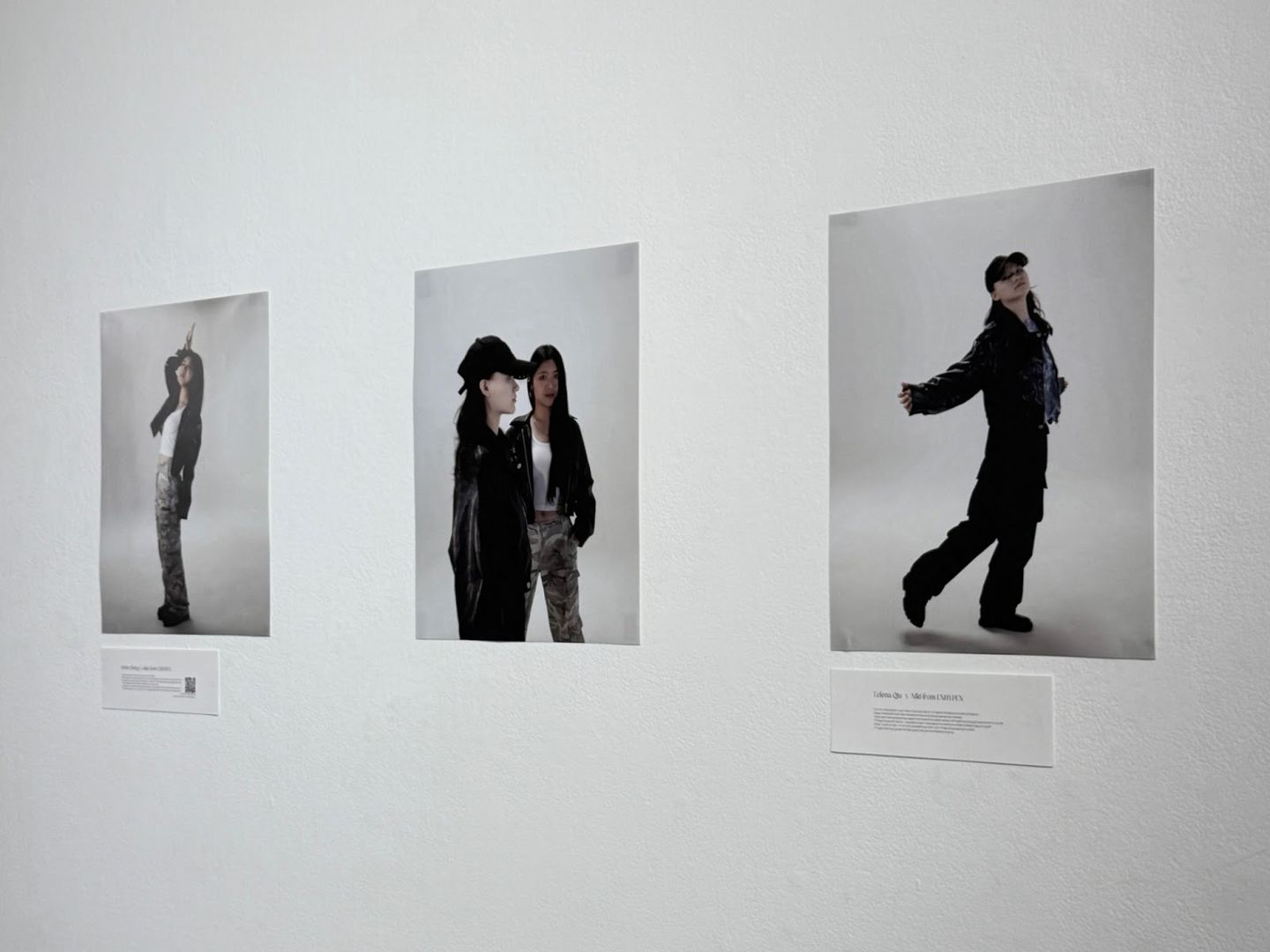

The exhibition, held at the Phyllis Gill Gallery at the University of California, Riverside, features striking photographic portraits of Asian American and non-Korean K-pop cover dancers across Southern California. Through these images, Moon pushes against reductive notions of mimicry. What she captures instead is performance as self-making—rooted in intention, rigor, and vulnerability.

Far from kinetic or hyper-performative, Moon’s portraits are composed with quiet restraint. Set against minimalist backdrops and captured in neutral lighting, each image focuses on gestures often overlooked in the spectacle of dance: the tilt of a chin, the delicate articulation of the hands, the poise held just before a pose breaks. The dancers are not mid-movement—they are mid-becoming.

“We weren’t interested in replicating the glamour of the stage,” says Moon. “I wanted to explore what identity looks like in process—how it’s negotiated through physical labor, emotional commitment, and aesthetic choices.”

This deliberate stillness reframes cover dancers not as passive fans, but as cultural agents—translators of transnational aesthetics, reinterpreting media with both reverence and autonomy.

Each portrait in the exhibition is accompanied by a brief personal reflection from the dancer featured—young performers who are not only the subjects of Moon’s photographs, but also collaborators in telling their own stories. These quotes function as micro-testimonies, illuminating how K-pop cover dance becomes a vehicle for empowerment, identity expression, and community formation.

“K-pop dance has helped me become more confident, revealing a side of myself I hadn’t shown before,” says Julia F., one of the participating dancers. For Natalie T., the practice created new dimensions of connection: “K-pop has not only given me a way to express myself, but also a way to meet and connect with people I would have never met otherwise… I grow as a performer by dancing and singing to the artists I love.”

Others describe the act of ‘covering’ as a means of reclaiming space. “For me, K-pop doesn’t just mean music and dance—it means friendship and self-confidence,” says Eelena Q. “When I cover an idol, I’m not only representing them—I’m also showcasing my skills. I’m glad that K-pop gives me that opportunity and confidence to do so.”

Moon’s work intervenes in broader discourses around Asian visibility in Western pop culture. For many participants, K-pop was the first time they saw Asian bodies celebrated on a global stage.

“I remember watching a K-pop video and thinking—Asian faces can be icons too,” recalls Irene Cheng. For diasporic youth, that realization wasn’t just about fandom. It was about possibility.

Moon’s photographs capture that shift—Asian American bodies not as recipients of culture, but as its co-authors. Her work complicates narratives of appropriation and authenticity, emphasizing the nuanced ways diasporic subjects engage with global media flows.

Moon situates the project within the fields of performance studies, dance ethnography, Asian American studies, and diaspora aesthetics. But more importantly, she constructs the work itself as an archive—a visual, scholarly, and performative resource that challenges who gets remembered, and why.

By drawing from her training across multiple disciplines, Moon ensures that the exhibition is not only compelling visually but deeply rooted in intellectual rigor. She is not simply documenting cover dance—she is reframing it as an academic and aesthetic practice worthy of serious inquiry.

In the age of algorithmic repetition, cover dances are often treated as disposable content—uploaded, liked, forgotten. But Becoming the Other, Becoming Myself resists that flattening. By relocating these performances from social media to a gallery wall, Moon asserts their cultural legitimacy.

“Photography becomes a form of preservation.”

“This isn’t just documentation—it’s a record of transformation, and of visibility earned through care and intention.”

The act of framing these dancers shifts the conversation. What is usually consumed as fleeting entertainment becomes a form of cultural memory.

Exhibited as part of a university-supported summer series, Moon’s project is not just a gallery show—it is a site of public scholarship. Open to students, faculty, artists, and the wider community, it invites interdisciplinary dialogue around identity, media, and performance.

Exhibited as part of a university-supported summer series, Moon’s project is not just a gallery show—it is a site of public scholarship. Open to students, faculty, artists, and the wider community, it invites interdisciplinary dialogue around identity, media, and performance.

Moon directly addresses gaps across multiple sectors: in dance scholarship, where diasporic K-pop dancers are often ignored; in art institutions, where their performances are rarely framed as serious cultural work; and in American narratives, where Asian identity is often seen as monolithic or foreign.

Her exhibition challenges these erasures, making space for diasporic Asian youth to be seen not as consumers of pop culture, but as producers of nuanced, affective, and creative expression.

Becoming the Other, Becoming Myself is a quiet but radical gesture—one that demands we take cover dancers seriously, not just as fans, but as authors of their own identities. It invites us to see the performance not as imitation, but as intention.

Yeji Moon’s project is ultimately about memory and authorship: who gets seen, who gets to perform, and who gets remembered. In giving these dancers a stage beyond the screen, she reframes cover dance as more than recreation. It becomes a form of diasporic writing—inscribed not with ink, but with movement, makeup, and the gaze of becoming.